Cynthia Williams

Special to Fort Myers News-Press

Dozens of articles have been published about Angela Melvin and Valerie’s House, the nonprofit she founded in 2016 with the mission to “help children and families work through the loss of a loved one together and go on to live fulfilling lives.” Doubtless, all who are familiar with Valerie’s House know that its founder named the organization after her mother, Valerie Melvin, who died in 1987.

But to fully appreciate Melvin’s vision — "that no child will grieve alone” — it is necessary to step inside the front door of the house in the Town & River neighborhood in Fort Myers on the afternoon of July 16, 1987, and to hear a child crying.

"Daddy, what's wrong?"

The 10-year-old is moving blindly through the house, screeching, her shrieks ear-piercing. Her face is flaming, the pupils of her eyes unnaturally dilated. But no matter how shrill her screams, she can’t beat back her father’s voice in her ears saying, “Your mother is dead.”

The child’s terror strikes her father’s heart like bright, flashing blades until finally he stops her, catches her in his arms and holds her tight, as her body, like a surging heart, kicks against his.

Angela: “My mother died July 16, 1987, around 3 p.m. She was on her way to pick my sister and me up from summer camp at the skating rink near what is now Six Mile Cypress and 41. She and her friend had been at Fort Myers Beach on what was one of my mom’s rare days off [work]. They had stopped at my dad’s furniture store near Summerlin and Gladiolus. After leaving there, they took Gladiolus to 41.”

Valerie Melvin was killed when her friend drove across the center line on “dead man’s curve,” just west of Lakes Park, and collided head on with a pick-up truck.

Angela and her little sister, Lisa, waited almost an hour for their mother to pick them up that afternoon. Their summer camp counselors began making phone calls and a while later, the girls’ grandmother arrived. Told them she was taking them home with her until their mother was found.

They were playing in their grandmother’s yard when their uncle drove up. Angela’s father got slowly out of the passenger side of the front seat. As he approached his daughters, they could see he had been crying. The girls clutched at him. “Daddy, what’s wrong? Daddy, where’s Mommy?”

Angela: “He walked my sister and me in the house and sat us down in the bedroom and told us, ‘Your mother is dead.’

“That night, lying in bed beside Lisa, I asked my father, ‘Are you sure she isn’t coming back?’ And through tears he said, ‘Yes, I’m sure.’”

To be told that the mother you saw in the morning is dead in the afternoon of the same day is a physical sensation. It’s like having your brain ripped from your skull. It’s like blacking out.

Learning to grieve

Angela was a freshman at the University of Florida when she finally began to grieve the loss of her mother. She had not known what to do with her pain and fear, so she had locked them down tight, afraid that if they got loose, they might devour her.

She had not known that grieving should be a natural, healthy process, not a silent, hidden one. She had inferred, from the stoicism of her mother’s own parents, that she should not display her pain. That sorrow must be borne privately.

Angela: “I spent the majority of my childhood rarely talking about my mother. Because my mother died in the summer, it was a lot easier for me to hide what happened. This began the inner turmoil of hiding her death. I never wanted anyone to see me as ‘less than’ or weird. I just didn’t mention it.

“My dad never did, either. In fact, no one did. He cried for a little that first year, and certainly that first Christmas, but as time went on, the pictures of their wedding and our life with my mother came down from the shelves and off the walls of our home. He started dating again. He remarried. My mother was rarely spoken of again.

“I’ve asked my dad why he never talked about my mother to us. He told me it was too hard. He said no one ever brought her up to him either. We all grieved in silence. We all grieved alone.”

Through her middle and high school years, Angela stayed feverishly busy. She had a lot of friends and extracurricular activities. She studied hard, driven to excel, dreaming of doing grand things in a world far from Fort Myers.

Angela: “I was a big dreamer…extremely ambitious. Grief experts say that whatever a child was like before the death often becomes exaggerated or on overdrive after the death. After my mom died, I became an overachiever.”

In June 1998, Angela’s brand new degree in journalism and communications, along with a good measure of brazen determination, landed her an on-air job at an ABC station in Columbus, Georgia. Over the next 10 years, she also worked in television stations in Tennessee, the Florida panhandle, and West Palm Beach.

Angela: “It was while working in Tennessee in 2003 that I heard about a special grief camp for children. I became a counselor that summer. It was the first time in my life that I saw how children in pain connected and needed each other, needed to talk about their loss. A seed was planted in my mind.”

It was while working at the NBC station in West Palm Beach that Angela discovered a little house for grieving kids called, “Hearts and Hope.” Angela met the director and toured the house with the intention of becoming involved in the program, but instead, she accepted the position of communications director in Washington, D.C. for a friend who had just won a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives.

A dream come true

Two years later, Angela decided she needed a break and that, as “it had been almost 20 years since I left Fort Myers, maybe I needed to go spend some time with my family.”

To the great good fortune of generations of children to come, Angela Melvin moved back to Fort Myers in 2012, and while working as a TV traffic anchor in the early mornings and managing a local chapter of Big Brothers Big Sisters, began looking for a grieving child to spend time with. Ironically, she had no idea where to find one.

Then she met a 6-year-old girl named, Camryn, whose mother had died from a sudden brain aneurysm. When her father said helplessly to Angela, “We don’t know where to go or what to do,” her heart broke.

That was it. Time to act. She had no idea how, but she had to do something for grieving families.

She began to scribble the words, “Valerie’s House,” in a notebook she carried around with her. She began to keep notes on what Valerie’s House would be like, and what it would take to build it.

Angela: “I wanted a safe place where kids could be themselves and talk about their grief, instead of bottling it up for years like I did. I also didn’t want children to feel ashamed of their loss or that they were somehow broken. I wanted them to see they weren’t alone, and that it was OK to grieve, to share memories.

“One day when I was telling someone about Valerie’s House, I said ‘It will be a place where they learn that loss doesn’t have to limit their dreams.’ I said that off the cuff, as I remembered having big dreams when I was little. My dad told my sister and me that we could still have everything we wanted out of life, despite our mom being gone. That really helped me believe in myself.”

At first, Valerie’s House was nothing but the scattered pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, but in 2014 and 2015, with help from her friends, Angela began to snap the pieces together and her dream began to take shape. When a businessman, Stephen Bienko, offered her his home in historic Dean Park, the dream became reality.

Angela: “As soon as I walked in, I knew it was Valerie’s House. It was built in the early 1900s and had such a special feel, a lot of light, high ceilings, and separate rooms for the kids to meet. It even had a backyard area where they could hang out.

“Valerie’s House scheduled its first grief support group in January 2016. I wondered if anyone would actually show up. Boy, did they ever. That first night we had 25 children and their parents.

“To date, we have had more 1,000 children and their families come through Valerie’s House. We have added a house in Naples and started a group in Punta Gorda in 2019. Next year, we will open a Valerie’s House in Pensacola.

“We have grown from a small volunteer staff to a professional staff of 10, including three licensed social workers and counselors. Some of the kids who started with us four years ago are mentoring grieving children in our program today.”

And, “We have been gifted a one-acre parcel by the city of Fort Myers to build our dream home and headquarters!”

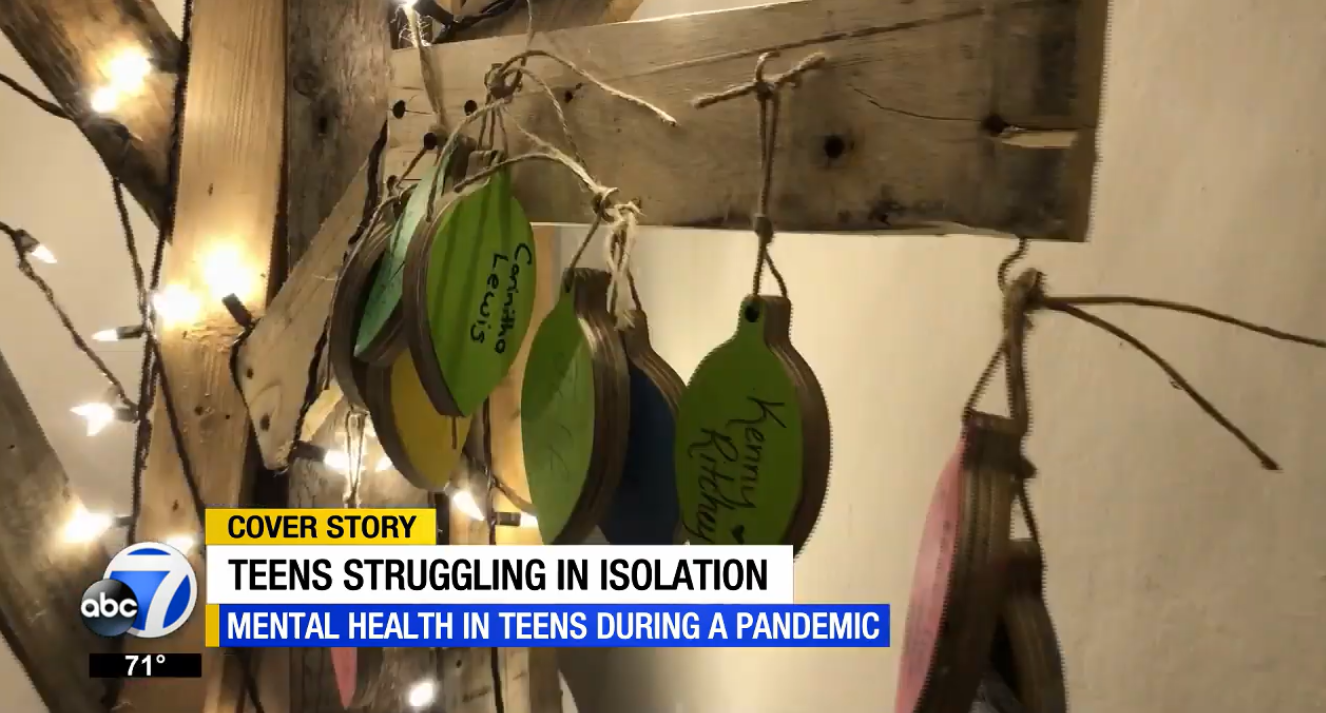

When children are asked how Valerie’s House has helped them, the answer is essentially the same, always. “It has taught me that I am not alone,” “given me friends and a family,” “taught me how to open up,” “helped me find my voice,” “changed my life forever,” and sweetest of all, “Valerie’s House saved me.”

“My dream,” says big dreamer Angela, “is that Valerie’s House will always be a place for grieving children, even well beyond my lifetime. Children will never have to grieve alone again.”

To read the short, remarkable history of Valerie’s House, to meet the staff and the children, to learn about its programs and plans for the future, please visit valerieshouseswfl.org.